The 1716 Advent cantata Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben (text by Salomon Franck, BWV 147a) is completely overshadowed by Bachs 1723 ‘remake’ for the Feast of the Annunciation (next to recitatives he also added the choral-variation jesu joy – BWV 147). However, a reconstruction is simple and musically worthwhile.

Only the aria for bass Ich will von Jesu Wundern singen from BWV 147 (nr. 9) has to be re-texted completely. For the rest only minor changes. Simply use the scheme below (bold is where the original differs), place the original text below the notes and you will notice that it perfectly fits the music. And : in the bass-aria text and notes even fit better: The signal-like theme of BWV 147/9 now sounds natural, logical, since the text refers to John the Baptist “a voice that crieth in the wilderness…”.

Below the text a more thorough assessment of the provenance, since there is some confusion. I suggest for instance – contra the scholarly consensus – that not only the first (autograph), but all 6 parts date back to Weimar.

Advent 2016 / Dick Wursten

The text of 147a and 147 juxtaposed

Below the original text (as published by Franck in 1717). Differences are bold (original 1717 ) and italics (refurbished 1723). Below the text two comments on ‘why’ the changes.

| BWV 147a | BWV 147 |

|---|---|

| Text: Salomo Franck (Weimar) | The numbers refer to the opening choir and the arias from 1723 |

| 1. CHOR | 1 |

| Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben Muß von Christo Zeugnis geben Ohne Furcht und Heuchelei, Daß er Gott und Heiland sei. | |

| 2. ARIE (alt) | 3 |

| Schäme dich, o Seele, nicht, Deinen Heiland zu bekennen, Soll er seine Braut* sich nennen Vor des Vaters Angesicht! Doch wer ihn auf dieser Erden Zu verleugnen sich nicht scheut, Soll von ihm verleugnet werden, Wenn er kommt zur Herrlichkeit. | …. dich die seine |

| 3. ARIE (tenor) | 7 |

| Hilf, Jesu, hilf, daß ich auch dich bekenne In Wohl und Weh, in Freud und Leid, Daß ich dich meinen Heiland nenne Im Glauben und Gelassenheit, Daß stets mein Herz von deiner Liebe brenne. Hilf, Jesu, hilf! | |

| 4. ARIE (sopraan) | 5 |

| Bereite dir, Jesu, noch heute die Bahn, Beziehe die Höhle ** Des Herzens, der Seele, Und blicke mit Augen der Gnaden mich an! | … itzo die Bahn, Mein Heiland, erwähle Die gläubende Seele Und siehe mit Augen... |

| 5. Aria (bas) | 9 |

| Lass mich der Rufer Stimme hören, Die mit Johanne treulich lehren, Ich soll in dieser Gnadenzeit Von Finsternis und Dunkelheit Zum wahren Lichte mich bekehren. | Ich will von Jesu Wundern singen Und ihm der Lippen Opfer bringen, Er wird nach seiner Liebe Bund Das schwache Fleisch, den irdschen Mund Durch heilges Feuer kräftig zwingen. |

| 6. CHORAL | — |

| Dein Wort lass mich bekennen Für dieser argen Welt, Auch mich dein’n Diener nennen, Nicht fürchten Gwalt noch Geld, Das mich bald mög ableiten Von deiner Wahrheit klar; Wollst mich auch nicht abscheiden Von der Christlichen Schar. | = Sixth Stanza from the choral: ‘Ich dank dir lieber Herre’. Simply use a 4vv chorale from 371 Choralgesänge (3 versions available) |

* In BWV 147 all references to the ‘bride-groom’ mysticism are suppressed. The imagery was appropriate in the context of Advent, where the arrival of the ‘groom’ is announced, coming to his ‘bride’ (Christ/Soul). One of the – for most modern readers invisible, incomprehensible- references to the Bride/Groom mysticis is the the phrase ‘Beziehe die ‘Höhle des Herzens ‘.

** The word ‘Höhle’ in nr. 4 refers to the text of Song of Songs, ch. 2, 14: My dove in the clefts of the rock, in the hiding places on the mountainside, show me your face, let me hear your voice; for your voice is sweet, and your face is lovely. In the allegorical mystical reading of the Song of Songs this invitation is linked to the wound in Jesus side, from which fled ‘water and blood’, salvific…(see f.i. Bernardus of Clairvaux’s sermon on this text, in which this imagery is used. It became ‘stock material’ for devotional literature since then, far into the 18th century.

The original (Leaf through this PDF, Sunday 4th Advent….)

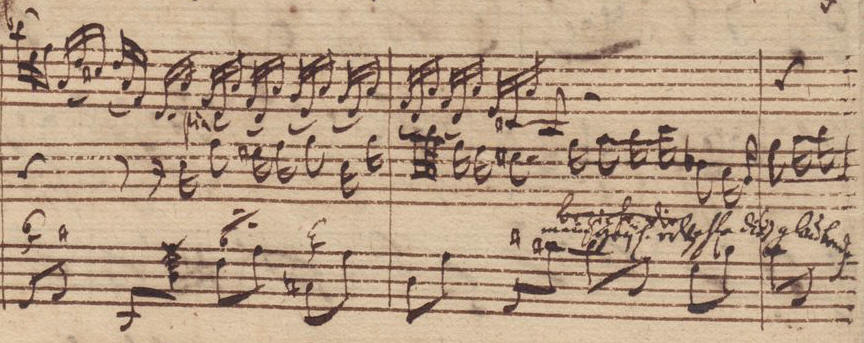

The original shimmers through in the autograph

Remarkable: in the autograph score of this Aria (BWV 147/5) the original wording of the second line is still recognisable (the first two words ‘beziehe die‘ are crossed out and are replaced by the phrase: mein heiland, erwähle die gläubende…. Did Bach suppress this reference to the Song of Songs himself last minute (slipped through in the general revision?). Or was he copying the original score and did he realize too late that this text should be replaced as well ? We’ll never know, but we are as close as we can get to Bach at work…

Provenance

Was the Weimar cantate ever completed by Bach or did he break up after part 1 (thesis of many scholars, e.g. Christoph Wolff) ? I don’t agree…

In the official source edition of the NBA (Neue Bach Ausgabe), one can read: Musik verschollen (Music lost). There are doubts whether Bach ever completed or performed the cantata. The libretto is ‘sure’, sinced it is published in 1717 by Salomon Franck himself. The score of BWV 147 (the 1723 cantata) is available in Bach’s own handwriting (the above is copied from that source). A fascinating detail: the paper can be dated ! So we now know

– the pages with the first movement of this manuscript (the opening chorus) date back to Weimar 1716.

– The movements 2-5 (until p. 6v) date from 1723

– the rest dates from 1728-32.

Christoph Wolff (Bach. Learned Musician, p. 164), following Alfred Durr, The Cantatas of J.S. Bach – English translation -, p. 15) infers from this state of affairs, that ‘Bach broke up the composition after mvt. 1’. This however is an example of jumping to conclusions based on reasoninge nihilo. In 1723 Bach had to break up at this point, because at that point new text was inserted and newly composed music had te be written down after the openingchorus. Ergo: the material evidence does not prove anything about the (non-)completion of the composition, let alone about the question whether is was performed or not. We have to leave that open, and present our opinions with the necessary caveats. The fact that the text of the bass-aria of 1723 exactly follows the metrical pattern of the text of 1716 rather suggests that Bach re-used the music in 1723. As suggested above: the signal-like theme also provides a clue that the music originally was conceived for the 1716 text.